![]()

Not a tile, a char neither a monster. The old friend of mine Boris, now in pixels.

![]()

Not a tile, a char neither a monster. The old friend of mine Boris, now in pixels.

Tons of new chars. I’ll not release them individually anymore because now I’m using just one XCF multilayer Gimp file that permits create of new char combinations, so I’ll be releasing this file instead.

Mathematically, let’s assume I have just one layer. This permits create just one character (the nude one), ok? Each new layer I create, earrings as example, permits me create all chars I have done before with and without those earrings. That’s 2 times what we had before. With N layers I can create 2n different chars (2n-1? No, a char made of no layers can be the invisible man:)). We have now about 50 layers so we can create more than one quadrillion different combinations of chars. 😮

Here’s the XCF Gimp file, chars.xcf (430Kb). To open and edit it you need the Gimp editor (The GNU Image Manipulation Program, download it here).

It’s also easier for you create your owns characters (try create yourself) or add hats, accessories, cloths, etc. Our My next step is write it to be programmability done with the same idea.

Tradução: há uma versão em Português desse artigo.

For some classes like javafx.scene.image.Image is easy load an image from a external resource like:

ImageView {

image: Image {

url: "http://example.com/myPicture.png"

}

}

or a resource inside your own Jar file with the __DIR__ constant:

ImageView {

image: Image {

url: "{__DIR__}/myPicture.png"

}

}

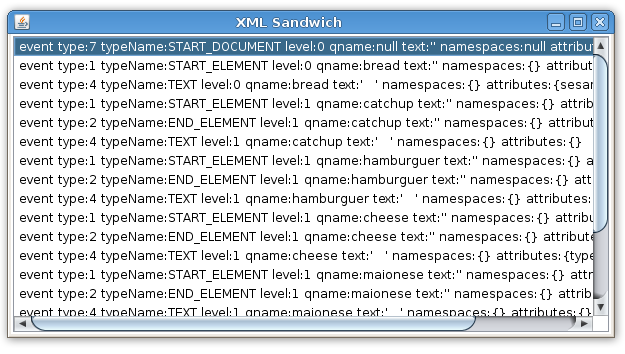

But for other classes loading a internal resource (inside your own jarfile) is not so direct. For example, in the article Parsing a XML Sandwich with JavaFX I had to place the XML file in a temp directory. A more elegant way would be:

package handlexml;

import java.io.FileInputStream;

import javafx.data.pull.*;

import javafx.ext.swing.*;

import javafx.scene.Scene;

import javafx.stage.Stage;

class Resource{

function getUrl(name:String){

return this.getClass().getResource(name);

}

function getStream(name:String){

return this.getClass().getResourceAsStream(name);

}

}

var list = SwingList { width: 600, height: 300}

var myparser = PullParser {

documentType: PullParser.XML;

onEvent: function (e: Event) {

var item = SwingListItem {text: "event {e}"};

insert item into list.items;

}

input: Resource{}.getStream("my.xml");

}

myparser.parse();

Stage {

title: "Map"

scene: Scene {

content: list

}

}

With a simple XML file called my.xml inside your package.

References:

More scenes and tiles for the free and open pixelart tileset. Also new monsters and characters but these will be showed in more details in another post.

Scientists discovery that they can’t keep a Gjelly (one of the new monsters) in cages.

And also a little medieval scene. A naive princess got a Nhamnham monster as her pet.

A new village scene, now with a pier, water, fence and new chars.

There’s a plenty of new tiles. Now that we have a good basic tiles becomes easy to add more tiles.

A work under progress. A first monster for a big set of monster I want to create. This one is called NhamNham.

NhamNham lives in forests and swamps and can be quite aggressive atacking with his forehead horn.

Here in this picture they organized a attack to a village and are been repealed by soldiers.

One more version of the my free tileset for game development. This little world is beautifully growing, now towards medieval themes. Now is already possible to imagine a typical day in a little rpg village:

And here the tileset, eighth version:

Changelog:

I got a simple motor from a broken domestic printer. It’s a Mitsumi m355P-9T stepping motor. Any other common stepping motor should fits. You can find one in printers, multifunction machines, copy machines, FAX, and such.

With a flexible cap of water bottle with a hole we make a connection between the motor axis and other objects.

With super glue I attached to the cap a little handcraft clay ox statue.

It’s a representation from a Brazilian folkloric character Boi Bumbá. In some traditional parties in Brazil, someone dress a structure-costume and dances in circular patterns interacting with the public.

Photos by Marcus Guimarães.

Controlling a stepper motor is not difficult. There’s a good documentation on how to that on the Arduino Stepper Motor Tutorial. Basically it’s about sending a logical signal for each coil in a circular order (that is also called full step).

Animation from rogercom.com.

You’ll probably also use a driver chip ULN2003A or similar to give to the motor more current than your Arduino can provide and also for protecting it from a power comming back from the motor. It’s a very easy find this tiny chip on electronics or automotive stores or also from broken printers where you probably found your stepped motor.

With a simple program you can already controlling your motor.

// Simple stepped motor spin

// by Silveira Neto, 2009, under GPLv3 license

// http://silveiraneto.net/2009/03/16/bumbabot-1/

int coil1 = 8;

int coil2 = 9;

int coil3 = 10;

int coil4 = 11;

int step = 0;

int interval = 100;

void setup() {

pinMode(coil1, OUTPUT);

pinMode(coil2, OUTPUT);

pinMode(coil3, OUTPUT);

pinMode(coil4, OUTPUT);

}

void loop() {

digitalWrite(coil1, step==0?HIGH:LOW);

digitalWrite(coil2, step==1?HIGH:LOW);

digitalWrite(coil3, step==2?HIGH:LOW);

digitalWrite(coil4, step==3?HIGH:LOW);

delay(interval);

step = (step+1)%4;

}

Writing a little bit more generally code we can create function to step forward and step backward.

My motor needs 48 steps to run a complete turn. So 360º/48 steps give us 7,5º per step. Arduino has a simple Stepper Motor Library but it doesn’t worked with me and it’s also oriented to steps and I’d need something oriented to angles instead. So I wrote some routines to do that.

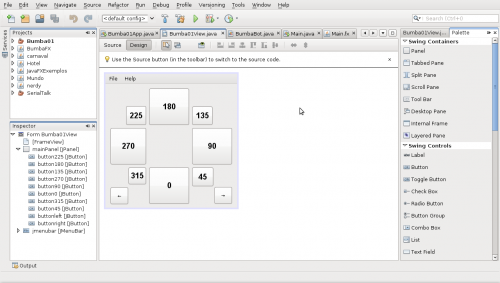

For this first version of BumbaBot I mapped angles with letters to easy the communication between the programs.

Notice that it’s not the final version and there’s still some bugs!

// Stepped motor control by letters

// by Silveira Neto, 2009, under GPLv3 license

// http://silveiraneto.net/2009/03/16/bumbabot-1/

int coil1 = 8;

int coil2 = 9;

int coil3 = 10;

int coil4 = 11;

int delayTime = 50;

int steps = 48;

int step_counter = 0;

void setup(){

pinMode(coil1, OUTPUT);

pinMode(coil2, OUTPUT);

pinMode(coil3, OUTPUT);

pinMode(coil4, OUTPUT);

Serial.begin(9600);

}

// tells motor to move a certain angle

void moveAngle(float angle){

int i;

int howmanysteps = angle/stepAngle();

if(howmanysteps<0){

howmanysteps = - howmanysteps;

}

if(angle>0){

for(i = 0;i

In another post I wrote how create a Java program to talk with Arduino. We'll use this to send messages to Arduino to it moves.Â

[put final video here]

To be continued... :)

Arduino is a free popular platform for embedded programming based on a simple I/O board easily programmable. Interfacing it with Java allow us to create sophisticated interfaces and take advantages from the several API available in the Java ecosystem.

I’m following the original Arduino and Java interfacing tutorial by Dave Brink but in a more practical approach and with more details.

Step 1) Install the Arduino IDE

This is not a completely mandatory step but it will easy a lot our work. Our program will borrow some Arduino IDE libraries and configurations like which serial port it is using and at which boud rate. At the moment I wrote this tutorial the version of Arduino IDE was 0013.

Step 2) Prepare your Arduino

Connect your Arduino to the serial port in your computer. Here I’m connecting my Arduino with my laptop throught a USB.

Make sure your Arduino IDE is configured and communicating well if your Arduino. Let put on it a little program that sends to us a mensage:

void setup(){

Serial.begin(9600);

}

void loop(){

Serial.println("Is there anybody out there?");

delay(1000);

}

Step 3) Install RXTX Library

We will use some libraries to acess the serial port, some of them relies on binary implementations on our system. Our first step is to install the RXTX library (Java CommAPI) in your system. In a Debian like Linux you can do that by:

sudo apt-get install librxtx-java

Or using a graphical package tool like Synaptic:

For others systems like Windows see the RXTX installation docs.

Step 4) Start a new NetBeans project

Again, this is not a mandatory step but will easy a lot our work. NetBeans is a free and open source Java IDE that will help us to develop our little application. Create a new project at File → New Project and choose at Java at Categories and Java Application at Projects.

Chose a name for your project. I called mine SerialTalker.

At the moment I wrote this tutorial I was using Netbeans version 6.5 and Java 6 update 10 but should work as well on newer and some older versions

Step 5) Adding Libraries and a Working Directory

On NetBeans the Projects tab, right-click your project and choose Properties.

On the Project Properties window select the Libraries on the Categories panel.

Click the Add JAR/Folder button.

Find where you placed your Arduino IDE installation. Inside this directory there’s a lib directory will some JAR files. Select all them and click Ok.

As we want to borrow the Arduino IDE configuration the program needs to know where is they configuration files. There’s a simple way to do that.

Still in the Project Properties window select Run at Categories panel. At Working Directory click in the Browse button and select the directory of your Arduino IDE. Mine is at /home/silveira/arduino-0013.

You can close now the Project Properties window. At this moment in autocomplete for these libraries are enable in your code.

Step 6) Codding and running

Here is the code you can replace at Main.java in your project:

package serialtalk;

import gnu.io.CommPortIdentifier;

import gnu.io.SerialPort;

import java.io.InputStream;

import java.io.OutputStream;

import processing.app.Preferences;

public class Main {

static InputStream input;

static OutputStream output;

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception{

Preferences.init();

System.out.println("Using port: " + Preferences.get("serial.port"));

CommPortIdentifier portId = CommPortIdentifier.getPortIdentifier(

Preferences.get("serial.port"));

SerialPort port = (SerialPort)portId.open("serial talk", 4000);

input = port.getInputStream();

output = port.getOutputStream();

port.setSerialPortParams(Preferences.getInteger("serial.debug_rate"),

SerialPort.DATABITS_8,

SerialPort.STOPBITS_1,

SerialPort.PARITY_NONE);

while(true){

while(input.available()>0) {

System.out.print((char)(input.read()));

}

}

}

}

Now just compile and run (with your Arduino attached in your serial port and running the program of step 2).

There is. Now you can make your Java programs to talk with your Arduino using a IDE like NetBeans to create rich interfaces.